Article by Irene Hilden, Jasmin Mahazi and Mèhèza Kalibani, on https://sammeln.hypotheses.org/2748 ,01 Dec. 2021

[Originally in: English]

Accessing Colonial Sound Archives: For a Plurality of Interpretations.

In Berlin, two sound archives emerged under colonial auspices and were part of the colonial project: the Lautarchiv at Humboldt University, which encompasses sound produced mainly in the heart of the German capital in the first half of the 20th century, and the Phonogramm-Archiv at the Berlin Ethnological Museum, with voices recorded in colonial territories and brought to the metropole by travelers or ethnologists. Along the years, these collections have contributed to a preservation of colonial structures of power and knowledge. As a way to engage with such voices, we discuss possible approaches to sonic legacies and reflect on the potentials and limitations of grappling with sensitive sound material. By outlining the institutional histories of colonial sound collections and focusing on two particular recordings, we address the double sensitive nature of historical audio sources. We aim to raise questions about the politics of access and presentation of sensitive sound material and argue for a plurality of interpretations of colonial sound archives.

African voices in the Lautarchiv

As we speak, in late 2021, the Lautarchiv is in a state of limbo: housed at Humboldt University until now, it will move to the highly contested Humboldt Forum. The decision to relocate the archive from the university to its namesake ‘forum’ remains ambivalent. On the one hand, the Lautarchiv has suffered from limited financial and human resources over the past decades, which meant that access was contingent on the courtesy of the staff in charge. The relocation gave hope that the call for lasting ethical care and a sustainable future for the archive’s holdings would finally be met. On the other hand, it is still unclear to what extent the archive’s collections will be accessible to international research communities in the future. Will (future) collaborations with various stakeholders also play a central role, besides the mere exhibiting of the archive at the Humboldt Forum? Considering the numerous non-white voices in the archive, this would indeed be much desirable.

Playing a shellac record in the Lautarchiv with a modern record player. The needle must be changed regularly to avoid abrasion. Photo: Irene Hilden

The archive’s core consists of more than 7,000 both original shellac records and duplicates, containing music and speech recorded between 1909 and 1944.[1] One of the oldest and most extensive archival collections of the Lautarchiv today are 1,651 recordings generated during World War I by members of the former Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission (Königlich Preußische Phonographische Kommission). Founded in late 1915, the Commission was set up to compile sound recordings of prisoners of war in German internment camps for linguistic and phonetic, musicological and anthropological purposes. Among the soldiers and civilian internees were several people from the colonies who fought for the British and French armies, but also some who had remained on German territory since the beginning of the war. For some of the Commission members, the voices of non-white people were of special interest. Not only was their research driven by colonial ideas in salvage anthropology and exoticism, it also meant that they could spare costly research trips and take advantage of the war situation to pursue their agenda in accumulating sound recordings.

After the war, the shellac records became part of the Prussian State Library’s newly founded Sound Department (Lautabteilung). While the so-called ‘war recordings’ provided the basis of the department’s holdings, one of its new aims was to systematically compile a collection of German dialects. Although it was no longer central to the department’s activities, researchers still occasionally recorded non-German languages. The archive, for example, contains sound testimonies of non-white diplomats and academics[2] who visited post-imperial Berlin, or of non-white artists who were exhibited/involved in so-called Völkerschauen [3].

At the beginning of the 1930s, the sound collections were again transferred, this time to the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin (today’s Humboldt University). From 1934 onwards, the archival holdings were located at the Institute for Sound Research (Institut für Lautforschung), directed by the Africanist Diedrich Westermann. During his incumbency, members of the institute recorded tongues spoken by the university’s African language instructors, such as Swahili and Ewe. Newly revitalized colonial aspirations under the Nazi regime meant that students who wished to enter colonial service should learn African languages, for which purpose African teachers were recruited.

Bayume Mohamed Hussein, German colonialism and the Nazi regime

The voice of Swahili language assistant Bayume Mohamed Hussein (or Husen)[4] dates from this period. The story of his life (and death) constitutes a powerful, exceptional but also heartbreaking example of the violent workings of German colonial entanglements.[5] Born in 1904 as Mahjub bin Adam Mohamed, Hussein was enrolled as a child soldier during World War I in the colony of German East Africa (today’s Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi). At the end of the 1920s, he came to Germany to demand pending payments for him and his deceased father’s service in the military. After the Foreign Office rejected his claim, Hussein began working as a waiter and actor in the exoticizing entertainment industry of Berlin. He also held the position of a language assistant at Berlin University, training prospective colonial administrators, officers and traders.

During his time in the German capital, Hussein constantly experienced racial discrimination and would ultimately not survive the prevailing racism that existed in the repressive Nazi state. Because he entertained intimate relationships with white women, the Gestapo arrested him in 1941, without trial. After three years of imprisonment in the concentration camp Sachsenhausen, he was killed by the Nazis in November 1944. In 2007, a tripping stone – Stolperstein – was inaugurated in front of his family’s last residence in Brunnenstraße in Berlin. It was the first commemorative stone dedicated to a Black victim of Nazi terror and persecution since the inception of this decentralized memorial project.

Why ‘collective listening’?

Hussein’s voice was recorded in 1934. In this recording, Hussein reads out a text in Swahili. Today, this recording constitutes a compelling, yet ambiguous trace of a colonial subject in the metropole. Compelling because it appears as a material and sonic expression of a Black person living and working in Berlin. Ambiguous, since this powerful recording was produced and archived in an institution of hegemonic colonial power – i.e. the university – and because listening to his voice can be a poignant, but also unsettling experience.

The collective listening workshop on ‘Academic Silencing’ was organized by Irene Hilden and Jasmin Mahazi at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin in 2019. Photo: Artur Gerke

Two authors of this article, Irene and Jasmin, wanted to engage with Hussein’s recording collectively, revolving around the question: how could the post-colonial futures of the Lautarchiv look like? So we organised a workshop as part of Irene’s broader research on the Lautarchiv’s colonial collections.[6] In order to allow for diverse interpretations of this recording, we invited several Swahili speakers, including specialists in Swahili studies and members of the Swahili-German diaspora. The rationale was not to repeat an act of epistemic violence by perpetuating an exclusive power over interpretation. The workshop facilitated collaborative, sensitive and affective engagement with this historical source and brought together different expertises, perspectives and positionalities.

Power and peril of sound: the double sensitivity of oral colonial sources

“Sound cannot be sounding without the use of power.“

(Walter J. Ong) [7]

Whenever one plays a sound recording from colonial times, there is always the danger of re-producing violence, for the recording is burdened with the weight of racial hierarchy, injustice and power relations.

During our ‘collective listening’ workshop, the hearers were strongly affected by Hussein’s voice pouring out into the room. To us listeners, it resonated with unease, detachment, hesitation, self-consciousness, insecurity, impersonality. We agreed that Hussein had to read out a text which he did not identify with. The act of recording thus it seemed was the product of iniquity and injunction.

Audio recordings from colonial times are sensitive historical objects, not only because of the unfair/unjust context of recording, but also because of the audios’ content. Bayume Hussein read out confidential information about marriage practices and customs during weddings. According to Swahili culture, some of these are even too intimate to be shared in public. The workshop participants estimated that this content must have come from a female informant and shared the opinion that such words should have only been articulated by a woman among women.[8] The sounding of these intimate details also aroused a sense of shame among Swahili-socialized listeners, all the more in a mixed gender group.

This sensitive aspect of the recording, however, cannot be simplified in terms of strict gender division, nor at the intersection of religious and gendered mores. To understand it, one has to look into particular modes of social interaction in the Swahili context. Embodied encounters imply that one seriously considers both heshima (honour/respect) and sitara (modest concealment), the latter being understood as protecting anything intimate from disclosure to a judging audience, and protecting it from arousing shame (-ona haya) in a more ‘public’ setting[9]. These descriptions of intimate nuptial practices conveyed through Hussein’s voice were unanimously identified by the workshop participants as a forceful intrusion into Swahili culture. Considering both the content and how this recording perpetuated a system of colonial knowledge production, the participants concluded that Bayume Hussein’s recording from the Lautarchiv should not be played.

Colonial recordings in the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv

The Lautarchiv is not the only archive in Berlin where sensitive sound recordings from colonial contexts can be found. Some of the scholars involved in the production of the Lautarchiv recordings had indeed first gained experience when making recordings for the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, another sound archive founded at the very beginning of the 20th century.[10] In fact, the Lautarchiv can be considered a ‘daughter’ of the Phonogramm-Archiv, which also holds recordings of German prisoner-of-war camps during World War I, namely 1,022 wax cylinders of music recordings produced by the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission. In total, the Phonogramm-Archiv is composed of almost 17,000 wax cylinder sound recordings produced between 1893 and 1954, a large number of which were generated in German colonies by ethnologists and colonial officers.

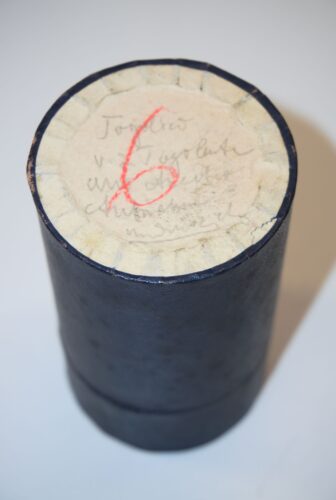

Wax cylinder ‘Waldow Kamerun 6’ in its case. Photo: Berlin Phonogramm-Archive

One recording from the Phonogramm-Archiv, labelled as ‘Waldow Kamerun 6’, reveals further issues related to sensitivity of, and access to, colonial sound archives. This historical source, which features several voices, was recorded in February 1907 by Hans Waldow in Lolodorf in the colony of German Cameroon, who was head physician of the Victoria Hospital at the time. The recording begins with an announcement by Waldow himself:

“Togo song sung by two Togolese people in Lolodorf. Recorded by Doctor Waldow. The song reads: ‘We are not many, but we can do whatever we want; the ants are small, but they can bite…’.“[11]

The voices of the two Togolese follow. They sing a song in Ewe language, spoken today in the West African countries of Togo, Benin and Ghana.

Listening to this recording, several aspects can stand under scrutiny: one may for instance focus on the announcer and his biography (Hans Waldow), on the history of migration of Ewe-speaking people from Togo to Cameroon, on Ewe language (e.g. maxims and proverbs in this song), on musicality (melody and rhythm), on the recording context (German colonial history in Cameroon and colonial knowledge production), or on the politics of memory (how can one experience or revisit the past). Depending on the subject matter, different approaches are possible: ‘auditive anthropology’[12], ‘close listening’[13], ‘archival silences as historical sources’[14], ‘listening to history’[15], and last but not least, ‘collective listening’[16].

Since listening is indeed an active practice, not a passive one, all these approaches imply an ethics, especially when dealing with colonial contexts. The practice of ‘collective listening’ proved as one possible way of “rethinking the politics of listening and producing knowledge”[17]. It enables us to learn about the past, but also to generate knowledge in the present. As shown above, sound recordings from colonial contexts should always be treated with caution, since these sound samples may remind listeners of the racist and colonial oppression their ancestors had to endure and therefore can offend people’s sensibilities. They are even liable to reproduce racist stereotypes. Some of the contents recorded and archived should obviously be played only on very particular occasions, uttered by particular singers, and heard by particular audiences, as in the case of Hussein’s recording. Ewe songs and proverbs are themselves also embedded in social and ritualistic practices. These recordings hence force us to consider different knowledge traditions, epistemologies and concepts of social interaction, and to operate a return to current political and social issues such as racism. In order to mend the wounds of colonial oppression, to go against hegemonic hoarding of such knowledge and to tackle post-colonial “epistemic injustice”[18], an ethics of listening means to create a more inclusive sphere in which different listeners can interact, deeply considering but also engaging with boundaries such as race, gender and scientific authority.

‘Collective ownership’ and politics of access

As we advocate for a plurality of interpretations of sound recordings from colonial contexts to unfold their various meanings and understandings, this also implies rethinking politics of access and presentation when curating these collections. Given the current debates about colonial histories and their legacies, it is about time for European sound archives to share these recorded bodies of knowledge with the people and institutions from their culture of origin. Clearly, Bayume Hussein was never truly the owner of his own voice when he read about nuptial practices. But today, who cares for his utterance? Can we speak of ‘collective ownership’, just as we speak of ‘collective listening’? One could argue that sound recordings – even those generated in colonial contexts – belong to the institutions where they have been produced, namely the Lautarchiv and the Phonogramm-Archiv. However, what has become clear from our research is that if one considers the voice of the speaker or singer as part of their body, if one engages with the colonial power relations under which these voices were recorded, these recordings then belong to those singers and speakers, and hence, their descendants. In the case of the so-called ‘Waldow recording’, this would mean the people of Lolodorf in Cameroon, and the people of Aného in Togo.

So why not consider these sound recordings as ‘shared heritage’? Not in the logic of justifying the wrongful detention of cultural artefacts[19], but as a shared heritage that can be – symbolically and physically – truly shared and thereby follows Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy’s vision of a new relational ethics[20]. In practice this means to facilitate both shared research and co-curated, co-created spaces of knowledge that not only tell the entangled histories of these colonial sound recordings, but also allow a dialogue across traditions and epistemologies through listening to and learning from each other.[21]

Acknowledgements

This article is the result of a joint panel discussion as part of the workshop Colonial Collections in Berlin Universities at the Technical University of Berlin. We thank Yann LeGall and Malina Lauterbach for organizing the workshop and inviting us to write this article. Their valuable comments and editing of the text were extremely helpful. Our thanks also go to Sarah Elena Link for her editorial work.

Authors

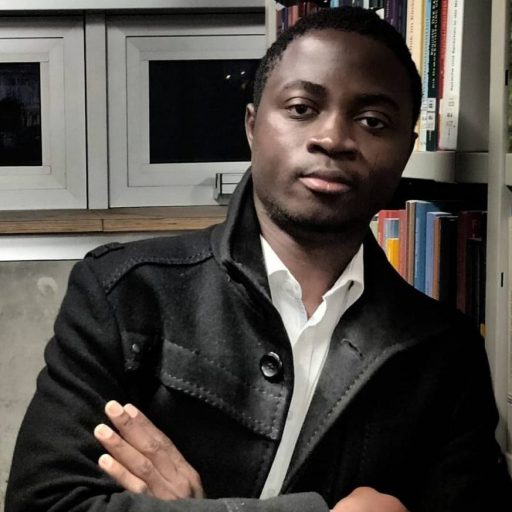

Irene Hilden is a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Anthropological Research on Museums and Heritage (CARMAH) at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Her research is concerned with Germany’s colonial past and present, transnational mobilities, and the uneven structures of colonial entanglements throughout history.

Mèhèza Kalibani is a PhD-Candidate at the Institute for Didactics of History and Public History, University of Tübingen. His PhD-Project is about early sound recordings from the Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv which he examines as acoustic heritage from German colonialism.

Jasmin Mahazi is a DFG-funded postdoctoral researcher at the Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO), Berlin. Her research interests are oral archives and embodied knowledge practices along the Swahili coast.

References

[1] Other archival objects of the Lautarchiv include wax cylinders, commercial records, records made from gelatin or acetate, photographs, phonetic instruments, and specialized literature.

[2] The most prominent example is probably a sound recording made in 1921 by the Bengali poet, writer and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore (or Thakur). Other examples include the recordings of the Chinese student Xiao Weixin (recorded in 1926) and the Siames diplomat Luang Bairai Bakya Bhakdi (recorded in 1927).

[3] See Irene Hilden: Die historischen Sammlungen des Berliner Lautarchivs. Zum Umgang mit akustischen Objekten. In: Ernst Seidl, Frank Steinheimer, Cornelia Weber (ed.): Materielle Kultur in universitären und außeruniversitären Sammlungen, Gesellschaft für Universitätssammlungen e.V., Berlin, 2018, p. 45-52 https://edoc.hu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/18452/19229/07_hilden.pdf?sequence=1 (last accessed December 1, 2021) and Irene Hilden: Absent Presences in the Colonial Archive. Dealing with the Berlin Sound Archive’s Acoustic Legacies. Leuven University Press, Leuven, forthcoming.

[4] In German post-colonial academic and public discourse, he is still often called Mohamed Husen – in amicable adjustment to his, more or less, voluntary choice of adapting his fellow German contemporaries’ pronunciation of his surname. It is our choice to use his name the way it was and is pronounced in his mother-tongue and within his fatherland.

[5] For further literature on his biography, see e.g. Bastian Breiter: Der Weg des ‘treuen Askari’ ins Konzentrationslager. Die Lebensgeschichte des Mohamed Husen. In: Ulrich van der Heyden, Joachmin Zeller (ed.): Kolonialmetropole Berlin, Berlin Edition, Berlin, 2002, p. 215-220; also Eva Knopf: Die Suche nach Mohamed Husen im kolonialen Archiv. Ein unmögliches Projekt. In: Eva Knopf, Sophie Lembcke, Mara Recklies: Archive dekolonialisieren. Mediale und epistemische Transformationen in Kunst, Design und Film, Transkript, Bielefeld, 2018, p. 83-106; Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst: Treu bis in den Tod. Von Deutsch-Ostafrika nach Sachsenhausen – Eine Lebensgeschichte, Ch. Links, Berlin, 2007; Katharina Oguntoye: Eine afro-deutsche Geschichte: Zur Lebenssituation von Afrikanern und Afro-Deutschen in Deutschland von 1884 bis 1950, Hoho Verlag, Berlin, 1997.

[6] Irene Hilden’s research not only investigates the practices and historical figures involved in the making of sound recordings, but moreover inquires into the epistemic framework of the German colonial knowledge regime and its legacies.

[7]Walter J. Ong: Orality, Literacy, and Modern Media. In: David Crowley, Paul Heyer (ed.): Communication in History. Technology Culture, Society, Longman, New York, 1999, p. 65.

[8] For more on the role of women within colonial recording practices and knowledge production, see Irene Hilden: Collective Listening. Tracing Colonial Sounds in Postcolonial Berlin. In: Kylie Crane, Sara Morais dos Santos Bruss, Lucy Gasser, Anna von Rath (ed.): The Minor on the Move. Doing Cosmopolitanisms, edition assemblage, Münster, 2021, p. 210-213.

[9] See Paola Ivanov: Die Verkörperung der Welt – Ästhetik, Raum und Gesellschaft im islamischen Sansibar, Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin, 2020.

[10] For example, the German medical doctor and linguist Otto Dempwolff (1871-1938) who recorded Malay speaking prisoners in the German POW camp in Berlin Ruhleben in April 1917 made his first recordings in German colonies between 1906 and 1911.

[11] The original in German reads: “Togolied, gesungen von zwei Togoleuten in Lolodorf. Aufgenommen von Dr. Waldow. Das Lied bedeutet: ‘Wir sind nicht viele, aber wir können doch tun, was wir wollen; die Ameisen sind klein und sie beißen doch…’.”

[12] See Hein Schoer, Bernd Brabec de Mori, Matthias Lewy: The Sounding Museum. Towards an Auditory Anthropology. In: Soundscape. In: The Journal of Acoustic Ecology, 2014, 13, p. 5-21.

[13] See Britta Lange: History and Emotion. The Potential of Laments for Historiography. In: Herbert Bley and Anorthe Kremers (ed.): The World during the First World War, Klartext-Verlag, Essen, 2014, p. 371-376; and Anette Hoffmann: Introduction. Listening to Sound Archives. In: Social Dynamics. A journal of African Studies, 2015, 41 (1), p. 73-83.

[14] See Britta Lange: Archival Silences as Historical Silences. Reconsidering Sound Recordings of Prisoners of War (1915–1918) from the Berlin Lautarchiv. In: Sound Effects. An Interdisciplinary Journal of Sound and Sound Experience, 2017, 7 (3), p. 47-60.

[15] See Daniel Morat, Thomas Blanck: Geschichte hören. Zum quellenkritischen Umgang mit historischen Tondokumenten. In: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht, 2015, 11/12, p. 703-726.

[16] See Irene Hilden: Collective Listening. Tracing Colonial Sounds in Postcolonial Berlin. In: Kylie Crane, Sara Morais dos Santos Bruss, Lucy Gasser, Anna von Rath (ed.): The Minor on the Move. Doing Cosmopolitanisms, edition assemblage, Münster, 2021.

[17] Ibid. p. 204-205.

[18] In her book, Miranda Fricker observes not only that “social disadvantage can produce unjust epistemic disadvantage”, she also claims that “hermeneutical injustice is caused by structural prejudice in the economy of collective resources”. Miranda Fricker: Epistemic Injustice. Power and the Ethics of Knowing, Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 1-2.

[19] See Kwame Opoku: Looted/Stolen Cultural Artefacts Declared “Shared Heritage”, 2015. https://www.no-humboldt21.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Opoku_SHARED_HERITAGE-4..pdf (last accessed December 1, 2021).

[20] See Felwine Sarr, Bénédicte Savoy: The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics, 2018. Translated by Drew S. Burk. http://restitutionreport2018.com/sarr_savoy_en.pdf (last accessed December 1, 2021).

[21] See e.g. Jasmin Mahazi’s current research project: Bahari yetu (our ocean/our genre): A matrifocal anthropological study of oral archives and embodied knowledge practices along the Swahili coast. https://www.zmo.de/forschung/hauptforschungsprogramm/lebensalter-und-generation/jasmin-mahazi (last accessed December 1, 2021)