Interview by Felix Gräfenberg, on https://hiko.hypotheses.org/1034 ,22. Apr. 2022.

[Originally in: German]

Interview with Mèhèza Kalibani

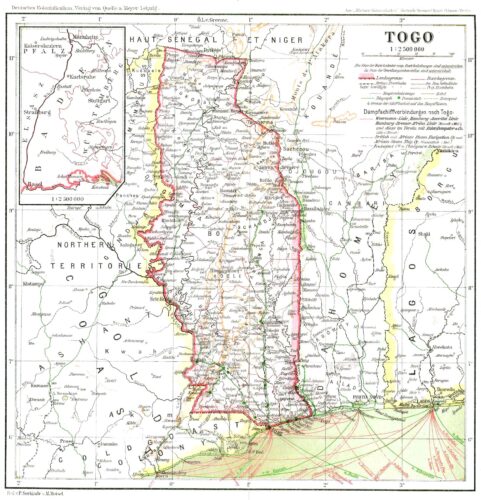

Mèhèza Kalibani came to Germany from Togo for his studies and doctorate. His research focuses on phonograms from colonial contexts in the Berlin Phonogram Archive. In this interview, he explains the added value of acoustic sources for historical research, reports on his research trip to West Africa ? and explains what all this has to do with Westphalia.

The interview took place digitally. Left: Mèhèza Kalibani, right: Felix Gräfenberg. (Photo: Felix Gräfenberg)

In your dissertation you deal with a rather unusual source genre, namely phonograms. I have the impression that even among historians in Germany these sources are largely unknown. Could you briefly explain what the Berlin Phonogram Archive is all about and what phonograms actually are?

Indeed, sound is the basic source of my investigations. In 1877, the invention of the phonograph made it possible to record and store sound. Phonograms were the accessories of the phonograph. On them the recorded sound was stored for playback. In the original they were made of wax in the form of rollers. It was not long before the apparatus was also used in German colonies. Thousands of the recordings made at that time are now in the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv. It was founded in the early 20th century and for decades commissioned the phonographic production of music and other recordings in non-European territories. This is where I start with my research.

Phonograph with wax cylinder (Photo: Berlin Phonogram-Archive

Wir Historiker:innen sind ja in der Regel vorrangig darin ausgebildet und geübt, uns mit Schriftquellen zu befassen. Welchen Mehrwert Siehst Du für die Kolonialgeschichtsforschung in der Auswertung dieser Phonogramme?

I consider the expansion of the source base to include acoustic sources as well to be extremely important and phonograms to be a thoroughly relevant source genre. Besides written sources, acoustic sources can also help us to understand and process certain aspects of history. The audible allows one to grasp history in a different way. They are not mere memories to be heard: They tell stories ? about people, about power relations, about the colonial system itself. The recordings are studied not only as such, but together with many other genres of sources such as written documents from the archives, correspondences, transcriptions of recordings, scholarly essays, family legacies, and so on. Moreover, the cultural dimension of these acoustic objects should not be underestimated, although one should be careful about that. They are a legacy from the past and potential sources on musical traditions of certain cultures that may have changed over time. So some recordings can be considered as cultural heritage in a certain sense.

How did you become aware of these colonial sound recordings?

That was purely by chance. I first learned about these recordings in 2017. It was through a friend who was studying at the University of Düsseldorf at the time. She was supposed to write a term paper and needed my help to translate a recording from Togo in the Tem language. I found it exciting to hear voices and music from the distant past and was also surprised at the same time that I had never known before that there were acoustic traces from the colonial era. I think that in Togo, where I come from, hardly any people know about it either.

Between 1884 and 1916 Togo was a German colony in West Africa (Map: public domain)

We have now talked mainly about a Berlin archive ? and about sources from West Africa. At first glance, that all has very little to do with Westphalia. Now, not only is the blog dedicated precisely to the history of this region, but you are also a member of the young researchers' network of the Historical Commission for Westphalia. That brings me to the question: What does your research topic have to do with Westphalia?

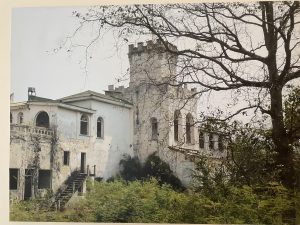

In my project, I am primarily interested in the contexts of the recordings, that is, the colonial power relations under which the recordings were made, what they were used for, whether they are authentic, and how they are dealt with today. In doing so, I examine photographs from seven collections. They are exclusively photographs taken by German colonial officials in German colonies. Among them is a rather well-known man from Westphalia: Julius Smend (1873-1939).

Would you like to tell us a bit more about this Julius Smend?

Very much so. That's quite funny: Two Julius Smend from Westphalia are reasonably well known from that time. Both are even related and were also interested in music. This always leads to confusion. The first (1857-1930) was a theologian from Lengerich, who later lived and worked in Münster. He published a lot about church music. I am not interested in him. The second Julius Smend, about whose collections I also work, was a lieutenant colonel and colonial officer. He is the father of the officer Günther Smend (1912-1944), who was executed on September 30, 1944 as a conspirator in the assassination attempt against Adolf Hitler. In any case, this Julius Smend was born in Recke in 1873 and died in Mülheim an der Ruhr in 1939. Between 1900 and 1906 he was a district officer and head of the police force in Togo under German colonial rule. He sent numerous "ethnological" objects and human remains from Togo to the then "Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde", today's Ethnological Museum in Berlin. objects and human remains from Togo. During this period he also made the sound recordings of songs and music of the colonized for the Berlin Phonogram Archive.

Why did Julius Smend record musical pieces and what was the purpose of his recordings in Germany?

Widespread at the time was the assumption that the culture of the natives was doomed to extinction by contact with Western actors. As part of a rescue rhetoric, European scientists assigned themselves the mission of collecting as much of the objects of the colonized as possible. In doing so, they saw themselves as a superior ?race? Immaterial objects such as images and sounds, whose acquisition required a technical process such as photography or sound recording, were also counted among the ?collected? objects. objects. The motive was by no means the supposed rescue of cultural assets. In Germany, the recordings also served to satisfy the curiosity of people eager to look and listen, who wanted to use them to form an impression of the colonized and their cultures. At large events such as the so-called ?Völkerschauen?, music from the colonies was also offered, often described as ?primitive? or ?exotic music? This confirmed racist assumptions and reproduced corresponding stereotypes. This created a bridge between colony and homeland and legitimized colonial rule. Julius Smend himself was fascinated by the different types of music played by the natives, as he wrote in his essays. Terms like ?primitive? and ?exotic? also appear again and again in his texts.

In so-called "ethnological shows" Africans, among others, were presented as "primitive" and/or "exotic" peoples in the large cities of Europe and North America. In the big cities of Europe and North America, Africans were presented as "primitive" and/or "exotic" peoples. (Postcard, around 1889, in the public domain)

In addition to this racist devaluation of Africans and their cultural objects by Europeans, the current debate about the treatment of material objects of colonial provenance often criticizes the fact that they were often created under violence. What about acoustic objects and their creation? What role did coercion and the use of violence play in the production of such recordings?

Similar to many other objects, it is difficult to understand what the direct recording situation was like and what made, moved, or encouraged the locals to make their voices heard in the phonograph hopper. Were they fascinated by the apparatus, were they forced to do it, or did they take it for granted? It is difficult to answer because of the paucity of sources. For one thing, the recorders rarely reported on the recording situation, and for another, no word was given to the colonized. But looking at the profile of the colonial officials themselves, it is clear in many cases that they were often not tolerant when the locals protested their orders. Many of them were involved in colonial scandals. This is also the case of Julius Smend, who led a bloody 'punitive' campaign against the colonized in 1907 because some of them objected to forced labor. So it is difficult to speak of voluntariness in the context of the creation of these recordings. In any case, it is necessary to clarify to what degree the colonial power relations played a role in this.

The emergence of the phonograms was characterized by the asymmetrical relationship of the recorder and the recorded ? even if the recording did not take place with the direct use of physical force. (German colonial master with natives, c. 1885, in the public domain)

Assuming that the recordings were made without direct use of force, how authentic are they? Were the recorders able to communicate with the colonized?

One cannot assume that. Most of the so-called ?collectors? did not know the local languages and if at all, then not so well as to be able to communicate well with the locals. They usually had to rely on the help of interpreters. Nevertheless, these were not always suited to the languages they had to interpret. In the Phonogram Archive, transcriptions and translations of the chants written by the recorders are also available to accompany the recordings. However, when examining these recordings and their transcriptions with the languages and cultures from which they originated, one notices that the translations or the written texts are often incorrect. Often, too, the meaning of the songs sung or the phrases spoken in the native culture is quite different from that given by the recorders. Whether this is due to the incompetence of the interpreters, a misinterpretation by the colonial official, or simply because it was explained incorrectly as a protest, must be found out in each case. That is why it is important to include the natives from the cultures of origin in the research of these recordings.

How do you manage to do that in your research?

Where possible, I try to incorporate impressions from people from the cultures of origin by talking to them about the recordings. I also get help in checking translations. Finally, I was in West Africa from the beginning of January to the end of February this year for fieldwork on the trail of a couple of recordings that I am examining in my dissertation project.

Where exactly were you there and what were you doing there?

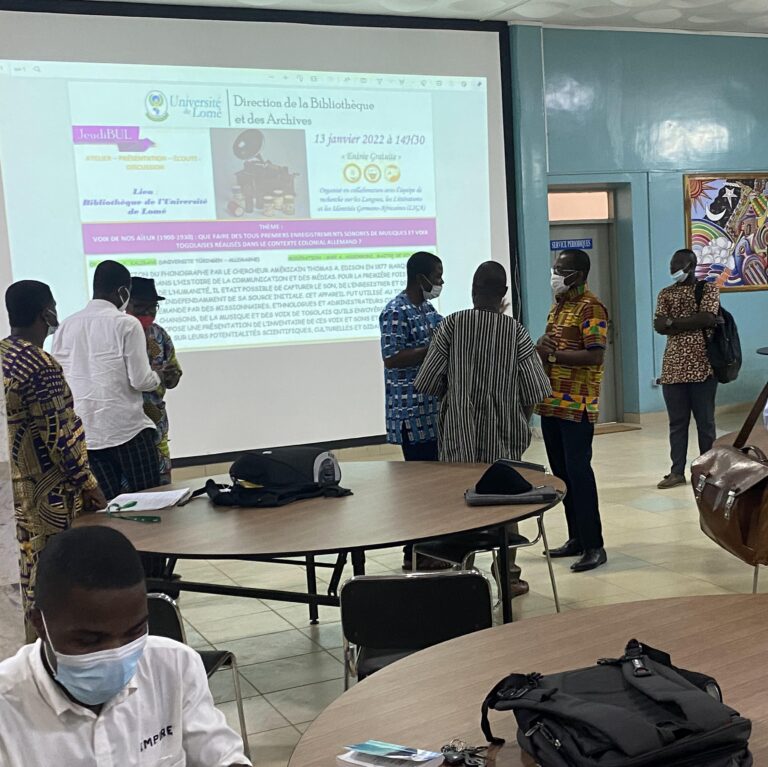

I was initially in several regions in Togo and Benin, as well as on the border between Togo and Ghana. In the capital of Togo, Lomé, I held a public workshop in January. The aim was first to present the collections about this country (there are a little more than two hundred individual photographs). The next part of the workshop concerned the discussion about the authenticity of the recordings. There was a collective listening, and deciphering of the content of the recordings. And after that, those present collectively discussed how to deal with these recordings today, and whether there would be interest for the archive to share them, which institutions would host them, who could access them, and how, what role these recordings could still play in Togo.

On January 13, Mèhèza Kalibani organized the workshop "Voix de nos aieux / Voices of our ancestors" in the reading room of the University Library of Lomé. (Photo: Mèhèza Kalibani)

In addition, I visited the National Archives and also conducted interviews with different actors on the ground, including artists and people working in the field of culture and archives, but also with kings. These were roughly about the possibilities that these recordings offer. For me, the collaborations with the artists were also very fruitful in another way: there are several pieces on the 'drum language' in the collections on Togo. Some of the artists I worked with are proven specialists in this field. This helped me a lot in the evaluation of the corresponding recordings.

In Yometschin, Mèhèza Kalibani exchanged views with locals about the colonial phonograms and how they are used today. (Photo: Mèhèza Kalibani )

His research trip also took Mèhèza Kalibani to the National Archives of Togo in Lomé for research purposes. (Photo: Mèhèza Kalibani )

In Benin, where I was also, I visited a few historical sites and also conducted interviews. In Cotonou, the capital of Benin, I had a professor who is a specialist of the sung language help me with the transcription and translation of a few sound recordings from the Smend collection.

Wie haben die Menschen auf diese Aufnahmen reagiert?

Genau wie ich damals 2017 in Düsseldorf waren die meisten Menschen, mit denen ich gesprochen habe, überrascht, von diesen Aufnahmen zu erfahren ? und darüber, dass diese erst jetzt, über 100 Jahre nach ihrer Entstehung, eine größere Bekanntheit erfahren. They were all very pleased with the results. At the workshop, participation in the discussion was very high. This was especially true for the artists. Im Allgemeinen habe ich den Eindruck, dass das Interesse an den Aufnahmen groß ist und dass die Menschen vor Ort in diesen Aufnahmen nicht nur musikalische Schätze oder akustische Zeuge der Vergangenheit, sondern auch, und vor allem, Quellen mit potentiellen didaktischen, und kulturellen Eigenschaften sehen.

Professional drummers of the talking drums at a funeral festival in Yometchin (Photo: Mèhèza Kalibani)

So should these recordings be returned? If so, in what form?

It is not surprising that many are often so surprised to learn about these recordings. Hardly people from the former colonies knew about it. Why is that? I think that for a long time the archive had closed the doors or hidden the recordings. Hidden' may sound harsh; in any case, the archives did not do enough to make these recordings accessible to people from the former colonies. By what miracle should someone in Togo or Cameroon come across these recordings, when almost all possible research channels have been exclusively in German for a long time, and searching the Ethnological Museum's online catalog does not allow filters by country and media type? What exactly is the archive doing to inform audiences outside Europe about the existence of these recordings? That's a question that currently can't be answered satisfactorily. They don't even have their own social media channels. As a rule, you only come across the collections by happy accident.

For pragmatic reasons, I would not talk about a return for the time being, because this would possibly require a longer process that would further delay making them accessible. Because returning would mean repatriating the original wax rolls. This would take more time because the wax cylinders have been entered into the register of world document heritage, recognizing the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation as the owner. So I would rather talk about sharing than returning. More than half of the over 16,700 early wax cylinder images in the archive have been digitized. Digitized items can be copied onto data media or sent by e-mail, and unlike material objects, this can be done without loss or special shipping costs. So if there is a will to share these recordings, there are undoubtedly many institutions in former German colonies that would be willing to receive them. But to do so, the people there would first have to learn about the existence of the recordings. And here, perhaps, the archive would have a long-neglected task to perform: Informing people outside Europe and opening its doors to them more widely than before.

Suggested Citation: Felix Gräfenberg, There and back again ? Von Westafrika nach Westfalen und wieder zurück, in: Westfalen/Lippe - historisch, 22/04/2022, https://hiko.hypotheses.org/1034.

Mèhèza Kalibani first studied German, Literature and Cultural Studies at the Université de Lomé in Togo (2010-2016). In 2016, he came to Germany from Togo for further studies in International Cultural Historical Studies in Siegen (2016-2019). Since 2019, he has been pursuing his PhD at the Institute for History Didactics and Public History at the University of Tübingen. He is a member of the Young Researchers Network on the History of Westphalia.

The topic of his dissertation project is: ?Verhörte(s) aus den deutschen Kolonien: On the (Post)Colonial Significance of the Acoustic Colonial Cultural Heritage Using the Example of Collections of German Colonial Officials in the Berlin Phonogram Archive?